The S Word: Getting to Grips with Sulfites and Wine

|

|

Time to read 13 min

|

|

Time to read 13 min

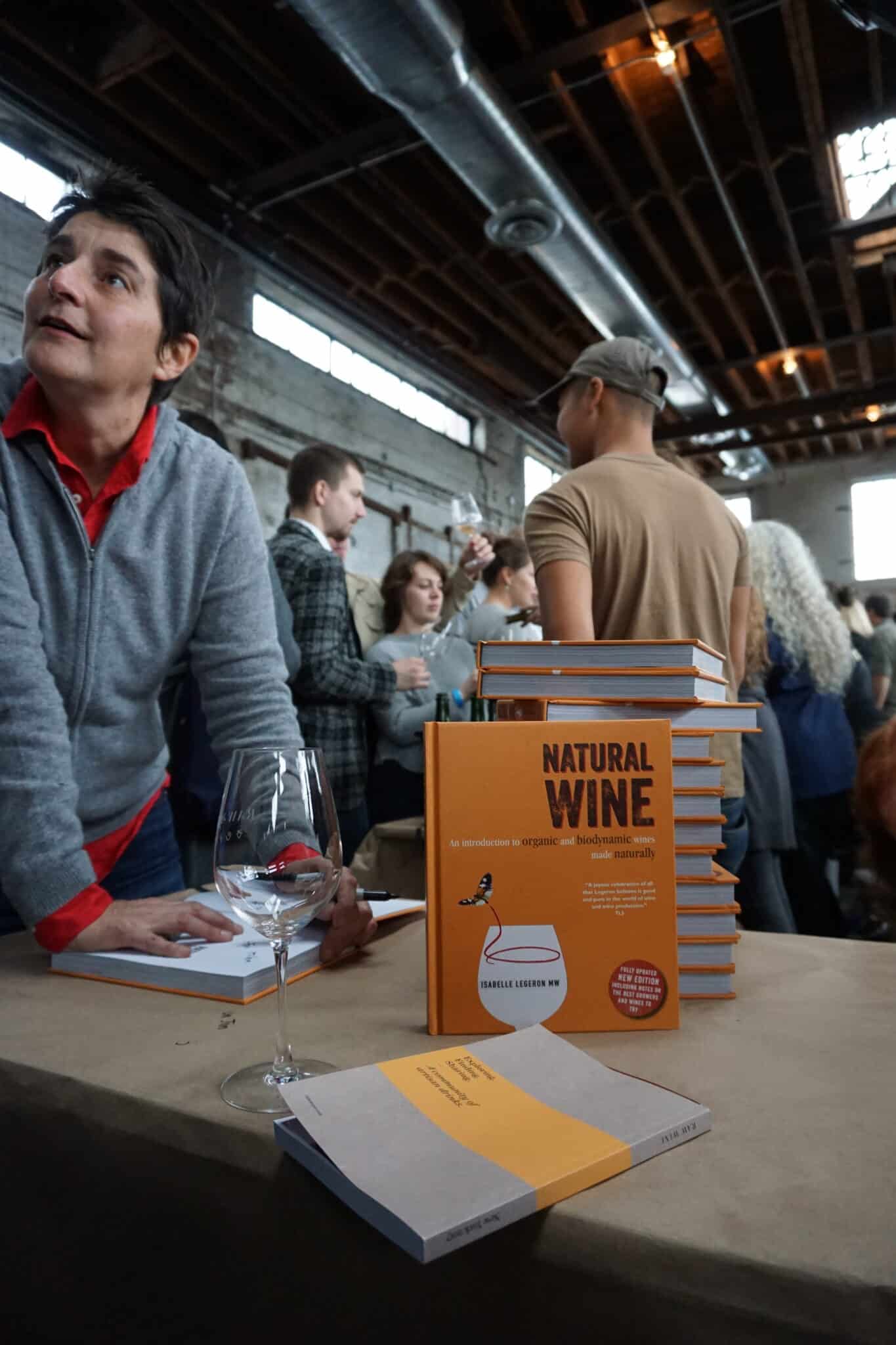

by Isabelle Legeron MW

The sulfite debate is one of the most heated, confused, and often misplaced topics in wine today. This is in large part due to the rise in popularity of natural wine, which has, in turn, fueled an interest in the use or non-use of sulfites, leading to drinkers mistakenly thinking that natural wine is really all about the act of not adding sulfites.

To confuse things further, while the focus of the debate is indeed the use (or overuse) of sulfites as a winemaking additive, a variety of alternate terms are bandied about in discussions as synonyms of sulfites when they are not, which has only served to muddy the waters even more.

Sulfur, for example, is one such word, and it is not uncommon to hear reference to unsulfured wines, whereas actually many natural wine growers may indeed use sulfur in the vineyard. Similarly, in natural wine circles, the term sans-soufre (French for ‘no-sulfur’) is often used, leading to even more confusion. So in order to set the record straight, let’s address semantics first.

Sulfur (or Sulphur, or Soufre in French)

Behind the scenes with Isabelle, filming a piece for the Travel Channel. Photo provided by Isabelle Legeron MW.

Although it can be found in its pure, native form (e.g. the yellow rock mined from volcanoes), most sulfur (or sulphur) occurs as sulfide and sulfate minerals. (The UK and Commonwealth spelling is “sulphur” while the preferred spelling officially adopted by the scientific community when referring to element 16 in the periodic table is “sulfur.”)

Most commercial sulfur is a byproduct of the petrochemical industry. It is commonly found in fertilizers, insecticides, and fungicides, and is widely used in vineyards as a blanket anti-fungal treatment against, for example, downy mildew (peronospora), in both organic and conventional viticulture. It is also used in the sanitization of winemaking vessels, such as wooden barrels and clay pots (qvevri / kvevri, anfora, tinajas, etc), in the form of sulfur wicks that are burned inside the vessels. The combustion of the sulfur produces sulfur dioxide which inhibits the development of bacteria and mold (more on sulfur dioxide and sulfites, below).

The French term sans-soufre—meaning “no-sulfur”—is actually an abbreviation for “sans dioxide de soufre ajouté” meaning, “no sulfur dioxide added.”

Sulfates (or Sulphates)

Sulfates are sulfur-based compounds that are salts of sulfuric acid. They are routinely used in the cosmetic industry (as a lathering agent in shampoo, for example) and in cleaning products. Some sulfate compounds are used in winegrowing and winemaking, including, for example, ammonium sulfate. Commonly used as a soil fertilizer and as an adjuvant to spraying insecticides; it is also used in the composition of flame retardants as well as a winemaking aid. Dissolved in water, it is used as a yeast nutrient and nitrogen source and added to the grape must.

Sulfides (or Sulphides)

Sulfides, or rather Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), are volatile sulfur-based compounds that cause the rotten egg smell associated with reduction in wine. They can occur as a byproduct of the fermentation process as sugar-loving Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeasts (wild or inoculated) transform the grape must. Sulfides can result during this process depending on factors like available nutrients or oxygen. It is a compound containing an anion (negatively charged ion) of sulfur, which, unlike sulfites, does not necessarily contain oxygen in the compound. Consequently, it is not used in winemaking for the purposes for which sulfites are used.

Sulfites (or Sulphites)

Sulfites are used as a food preservative thanks to their antibacterial and antioxidant properties. While they can be derived from elemental sources of sulfur, the vast majority of sulfiting agents are byproducts of the petrochemical industry. They are manufactured through the burning of fossil fuels and the smelting of mineral ores containing sulfur. Some of the chemical agents commonly used for winemaking to produce sulfites include sulfur dioxide, sodium sulfite, sodium bisulfite, sodium metabisulfite, potassium metabisulfite, and potassium hydrogen, to name a few (E220, E221, E222, E223, E224, and E228 respectively). As a group, they are generically referred to as ‘sulfites’ and ‘SO2’. They are often mistakenly referred to as ‘sulfur.’ It is this group of additives that has become the focus of much debate in the wine world in recent years.

Sulfur Dioxide (or SO2 or E220)

Sulfur dioxide is a chemical oxide that is closely related to sulfites—it is added to wines to produce sulfites. It has antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. As such, sulfites and sulfur dioxide are used interchangeably in the food and drink industries.

Sulfur dioxide occurs naturally during the fermentation process, as the sulfur-containing amino acids (methionine and cysteine) get metabolized by yeasts. Measured in ppm (parts per million) or mg/l (milligrams per liter), the production of this naturally occurring SO2 varies according to the strain(s) of yeasts present in the fermentation, ranging from as little as a few milligrams to more than 100 mg/L, according to Lallemand (one of the world’s largest commercial yeast developers).

It is also widely used as an additive throughout the winemaking process—as grapes enter the winery, added to the must, during fermentation, after malolactic fermentation, at racking, at bottling, to name but a few. While “generally regarded as safe” by the US Food and Drug Administration, maximum levels are controlled and dependent on the country of production as well as limitations set by certification bodies (organic, biodynamic, etc). These can be extremely confusing. For example, neither sulfur dioxide nor sulfites can be added to certified organic wine in the USA whereas, in Europe, they can.

To complicate matters, in winemaking, sulfur dioxide is expressed in terms of A) Free SO2, B) Bound SO2, and C) Total SO2, which is a combination of both the free and bound.

Free SO2 is an important measure as it is the active part of the additive—it is the free sulfur dioxide in the wine that will provide microbiological stability and prevent oxidation. Bound SO2 refers to the sulfur dioxide that bound to the sugars, acids, and anthocyanins when it was added to the wine. Both the free and bound totals are combined when calculating Total SO2 which is itself an important measurement as it is this total that is regulated by law. It provides an overall idea of how much sulfur dioxide is present in the final wine. This figure provides an insight into how much manipulation the wine has undergone, while also informing the drinker of how much they will be ingesting.

Sulfites are used to protect wine against the development of certain (so-called) faults—volatile acidity (VA), Brettanomyces (brett), mousiness, and oxidation, for example. While mousiness (a strong off-milk taste) is certainly to be avoided, a touch of VA (nail varnish), brett (farmyard), or a few oxidative notes (nuttiness) are in fact flirted with by many producers as they can add depth and complexity to a wine. This means that if you are working with healthy juice in a clean environment then the heavy-handed use of sulfites is really more a stylistic choice than anything else.

They are often used, for example, to prevent malolactic fermentation (mlf), which happens naturally on most wines if left to their own devices. During mlf, tart malic acid is transformed into the much softer, rounder, creamier lactic acid, so a conventional producer of Sancerre, for example, wanting to bottle a crisp, zesty, pale-white Sauvignon Blanc will likely have to use a protective, reductive winemaking process that uses sulfites at most stages of production.

Sébastien Riffault, a natural wine grower-maker in Sancerre, eschews sulfites on most of his cuvées and as a result, his wines are spicy, honeyed, and textured—a stark contrast to those made by most producers in his appellation.

One might argue that Sébastien’s wines are atypical of a Sancerre but then what really is a Sancerre? His wines are much closer to the expression of Sancerre that his grandfather would have known, for example. Sulfites only really became part of the winemaker’s arsenal in the latter part of the 20th Century. Contrary to popular belief their use is very recent indeed. The Romans, for example, did not use it. They used sulfur for cleaning purposes (to wash floors) but there is no evidence of it ever being used in winemaking. In fact, according to Paul Frey, of Frey Vineyards in Mendocino County who have been making sulfite-free wines for some 40 years, the earliest written references to sulfur and its use in the context of wine, date back to the 15th century when the German Emperor in Rothenburg od der Tauber decreed against what he saw as the adulteration of wine and severely restricted the burning of sulfur in barrels to approximately 10 mg/L, a minute dose by today’s standards. The sulfur, and resulting sulfur dioxide, mentioned was being used for barrel sterilization and not wine preservation. In fact, while the burning of sulfur wicks for sterilization became widespread over the course of the next 500 years, it was not until the early 20th Century with the development of the ‘Campden Fruit Preserving Solution’ and ‘Campden Tablet’ that it became possible to actually add sulfites into wine itself.

Fast forward 100 years (a blip in the 8000-year-old tradition that is winemaking) and nowadays sulfites are very commonplace and used by the vast majority of winemakers around the world. It is referred to as an essential additive and in fact, many believe that it is impossible to make decent (let alone great) wine without it. And yet what they do not realize is that many of the world’s most traditional estates—those who didn’t bow to fads or change their working methods over the course of time—employ little to no sulfites in their processes. So although it is the young, revolutionary winemakers that have made ‘natural wine’ headlines in recent years, the truth is that many prestigious domaines, such as Henri Bonneau & Fils, Château Le Puy or Domaine de La Romanée-Conti (DRC), have been doing it this way for centuries.

Fast forward 100 years (a blip in the 8000-year-old tradition that is winemaking) and nowadays sulfites are very commonplace and used by the vast majority of winemakers around the world. It is referred to as an essential additive and in fact, many believe that it is impossible to make decent (let alone great) wine without it. And yet what they do not realize is that many of the world’s most traditional estates—those who didn’t bow to fads or change their working methods over the course of time—employ little to no sulfites in their processes. So although it is the young, revolutionary winemakers that have made ‘natural wine’ headlines in recent years, the truth is that many prestigious domaines, such as Henri Bonneau & Fils, Château Le Puy or Domaine de La Romanée-Conti (DRC), have been doing it this way for centuries.

A few years ago, I was fortunate to drink a 1969 DRC Vosne Romanée over the course of a day. The wine started off closed and austere but after a while, in the glass, it began showing youthful vibrancy and an extraordinary aromatic complexity and depth. What was particularly notable was how alive and how fresh it was, despite its age, and how precise and crystalline its flavors were. It tasted very natural, which prompted me to call Bertrand Noblet, cellar master at the time, where I discovered that only some 20 mg/L had been added at bottling. Respectfully grown, fermented naturally, nothing added and nothing removed; only a dash of sulfites are added at bottling—it was indeed a natural wine.

And that is the crux of the issue—sulfites are an antimicrobial, and great wine is great in large part precisely because of its microbiology, which offers a slice of a place that arrives in the cellar on the grapes at harvest, works to transform the juice and is then bottled along with the wine, where it continues to live and transmit the sense of place from whence it came. So, if as a winemaker, you pump your drink full of an antimicrobial then your microbiology will inevitably suffer. How much, is directly proportional to the quantity which you add, but unfortunately, this information is not mandatory on a wine label (something we are working hard to raise awareness of and change at RAW WINE).

Since 1988 (USA) and 2005 (EU), all wines containing more than 10 mg/L total sulfur dioxide have to include ‘contains sulfites’ on the label, but the real question is how much is present. A truly natural grower, for example, who does not add any but whose wine contains 15 mg/L naturally, has to include the mention, as does an industrial producer, whose totals might be as high as 350 mg/L. In the EU, sulfite totals are legally permitted up to 150 mg/L, 200 mg/L, and 400 mg/L for red, white, and sweet wines respectively, while in the USA a blanket 350 mg/L limit applies. In short, as things currently stand, we have no idea what we are drinking, which is shocking not least because we don’t truly understand the implications on human health.

Although sulfites are generally regarded as a safe additive (except for those with asthmatic tendencies), few studies have examined them in the context of alcohol, which is very different from, for instance, applying sulfites on slices of fresh pineapple. Wine is alcohol, which when ingested has to be processed by the liver for excretion by the body. The issue seems to be that the liver may be inhibited in its activity by the presence of sulfites (see the chapter on ‘Sulfites and Health’ in my book Natural Wine: An Introduction to Organic and Biodynamic Wines Made Naturally for more information), and there is anecdotal evidence that this can lead to powerful headaches, something which appears to be avoided with natural wine.

This is one of the main reasons why the average drinker has started to question received wine wisdom in recent years, and why so many have taken to natural wine. It has better environmental credentials, a better claim at expressing a sense of place (even if the wine does not come from a great terroir), and even a likelihood of being better for your health not only on account of the clean fruit used but also because of the lack of sulfites. This in turn has made many conventional producers start to rethink their sulfite usage. Some now opt to simply change their methodology and do away with sulfites altogether by replacing them with other additives (lysozymes, ascorbic acid, potassium sorbate) or processes (flash pasteurization, sterile filtration, or ultraviolet radiation) that are perhaps even more interventionist than sulfites.

In our modern culture, wine has ceased to be a purely sensorial experience—an idiosyncratic foodstuff that we ingest—to become instead an intellectual exercise, which we have sought to control and duplicate. We have lost the appreciation that in its purest form wine is the magical result of a simple life-giving metabolic transformation enabled by nature’s way of creating life and death. Wine was originally a live drink and we tamed it into becoming a sterile, overly predictable lifeless beverage. And while the heavy-handed use of sulfites helps with this quest, trading them out for other additives and processes that do much the same thing, or indeed simply cutting them out without reassessing your whole growing and making journey completely misses the point. The most important thing, above all, is to get the farming right so that you have such a healthy harvest and an abundance of indigenous microbiology that doing away with the sulfites just takes a leap of faith.

And this can actually be the hardest part of all. “The biggest challenge is definitely your own mind and being able to let go, having the confidence to know that your wine is ready and can make it on its own, like a child,” explain natural wine grower-makers Eduard and Stephanie Tscheppe-Eselböck from Gut Oggau, a biodynamic estate in Austria that went sulfite-free on all its cuvées in 2009. “Some new producers nowadays take over a vineyard and produce no-added sulfite wines in their first year, but I’m not sure that is right,” continues Eduard, “the vineyard needs to be stable, in harmony, as then you have everything you need and it is only about your mind letting go.” The simple truth that many of us in the wine world seem to have forgotten is that as a South African winemaker once told me, wine makes itself.

Producing sulfite-free wines for the sake of producing sulfite-free wine to meet market demand is, in my opinion, a wasted effort, as what makes great no-added sulfite wine truly great is its genuine wholesome aliveness on the palate. There is a vibrancy and a purity of flavor that can’t be fudged or faked, which is why low-intervention, no-added sulfite wine from conventionally farmed grapes always falls short.

The secret is all in the farming and the pursuit of biodiversity, which is why deciding to make wine without any safety net has to be a choice led by awareness, respect, and trust—so that you can make that leap of faith knowing that the care you have given to your plants and soil will directly translate into more life and better wine-making.

Eschewing the use of sulfites and other additives while not compromising on the quality of your wine requires farming that nurtures an abundance of life in all its forms, rather than promoting the dominance of any one species. The result is then a panoply of organisms whose whole is far greater than the sum of its parts. In this endeavor being organic is just a starting point, like base camp on your way to climb Everest, the more you invest time and energy into nurturing the vineyard’s life, the more connected the plant will be to its environment and the better your wine will be. It is a never-ending virtuous circle.

Growing and making natural wine is therefore a choice based on wanting to produce a drink that pulsates with life, driven by a deep respect for both nature and life itself. Wines made like this are no-added sulfite wines, yes, but they are so, so much more than that too. They are what truly great wine is all about.